Which Terms Are Used To Identify The Lobes Of The Right Lung? Select All That Apply.

Community-acquired pneumonia is defined as pneumonia that is acquired outside the hospital. The most commonly identified pathogens are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, atypical bacteria (ie, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella species), and viruses. Symptoms and signs are fever, cough, sputum production, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, tachypnea, and tachycardia. Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation and chest x-ray. Treatment is with empirically chosen antibiotics. Prognosis is excellent for relatively young or healthy patients, but many pneumonias, especially when caused by S. pneumoniae, Legionella, Staphylococcus aureus, or influenza virus, are serious or even fatal in older, sicker patients.

The most common bacterial causes are

Pneumonias caused by chlamydia and mycoplasma are often clinically indistinguishable from other pneumonias.

Since the year 2000, the incidence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) skin infections has increased markedly. This pathogen can rarely cause severe, cavitating pneumonia and tends to affect young adults.

S. pneumoniae and MRSA can cause necrotizing pneumonia.

P. aeruginosa is an especially common cause of pneumonia in patients with cystic fibrosis Cystic Fibrosis Cystic fibrosis is an inherited disease of the exocrine glands affecting primarily the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems. It leads to chronic lung disease, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency... read more  , neutropenia Neutropenia Neutropenia is a reduction in the blood neutrophil count. If it is severe, the risk and severity of bacterial and fungal infections increase. Focal symptoms of infection may be muted, but fever... read more , advanced acquired immunodeficiency syndrome Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection results from 1 of 2 similar retroviruses (HIV-1 and HIV-2) that destroy CD4+ lymphocytes and impair cell-mediated immunity, increasing risk of certain... read more

, neutropenia Neutropenia Neutropenia is a reduction in the blood neutrophil count. If it is severe, the risk and severity of bacterial and fungal infections increase. Focal symptoms of infection may be muted, but fever... read more , advanced acquired immunodeficiency syndrome Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection results from 1 of 2 similar retroviruses (HIV-1 and HIV-2) that destroy CD4+ lymphocytes and impair cell-mediated immunity, increasing risk of certain... read more  (AIDS), and/or bronchiectasis Bronchiectasis Bronchiectasis is dilation and destruction of larger bronchi caused by chronic infection and inflammation. Common causes are cystic fibrosis, immune defects, and recurrent infections, though... read more

(AIDS), and/or bronchiectasis Bronchiectasis Bronchiectasis is dilation and destruction of larger bronchi caused by chronic infection and inflammation. Common causes are cystic fibrosis, immune defects, and recurrent infections, though... read more  . Another risk factor for P. aeruginosa pneumonia is hospitalization with receipt of IV antibiotics within the previous 3 months

. Another risk factor for P. aeruginosa pneumonia is hospitalization with receipt of IV antibiotics within the previous 3 months

A host of other organisms causes lung infection in immunocompetent patients.

Q fever, tularemia, anthrax, and plague are uncommon bacterial syndromes in which pneumonia may be a prominent feature. Tularemia Tularemia Tularemia is a febrile disease caused by the gram-negative bacterium Francisella tularensis; it may resemble typhoid fever. Symptoms are a primary local ulcerative lesion, regional lymphadenopathy... read more  , anthrax Anthrax Anthrax is caused by the gram-positive Bacillus anthracis, which are toxin-producing, encapsulated, facultative anaerobic organisms. Anthrax, an often fatal disease of animals, is transmitted... read more

, anthrax Anthrax Anthrax is caused by the gram-positive Bacillus anthracis, which are toxin-producing, encapsulated, facultative anaerobic organisms. Anthrax, an often fatal disease of animals, is transmitted... read more  , and plague Plague and Other Yersinia Infections Plague is caused by the gram-negative bacterium Yersinia pestis. Symptoms are either severe pneumonia or massive lymphadenopathy with high fever, often progressing to septicemia. Diagnosis is... read more

, and plague Plague and Other Yersinia Infections Plague is caused by the gram-negative bacterium Yersinia pestis. Symptoms are either severe pneumonia or massive lymphadenopathy with high fever, often progressing to septicemia. Diagnosis is... read more  should raise the suspicion of bioterrorism Biological Agents as Weapons Biological warfare (BW) is the use of microbiological agents for hostile purposes. Such use is contrary to international law and has rarely taken place during formal warfare in modern history... read more .

should raise the suspicion of bioterrorism Biological Agents as Weapons Biological warfare (BW) is the use of microbiological agents for hostile purposes. Such use is contrary to international law and has rarely taken place during formal warfare in modern history... read more .

Bacterial superinfection can make distinguishing viral from bacterial infection difficult.

Common viral causes include

Adenoviruses, Epstein-Barr virus, and coxsackievirus are common viruses that rarely cause pneumonia. Seasonal influenza Influenza Influenza is a viral respiratory infection causing fever, coryza, cough, headache, and malaise. Mortality is possible during seasonal epidemics, particularly among high-risk patients (eg, those... read more can rarely cause a direct viral pneumonia but often predisposes to the development of a serious secondary bacterial pneumonia. Varicella virus and hantavirus Hantavirus Infection Bunyaviridae contain the genus Hantavirus, which consists of at least 4 serogroups with 9 viruses causing 2 major, sometimes overlapping, clinical syndromes: Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome... read more cause lung infection as part of adult chickenpox and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Coronaviruses Coronaviruses and Acute Respiratory Syndromes (MERS and SARS) Coronaviruses are enveloped RNA viruses that cause respiratory illnesses of varying severity from the common cold to fatal pneumonia. Numerous coronaviruses, first discovered in domestic poultry... read more cause severe acute respiratory syndrome Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Coronaviruses are enveloped RNA viruses that cause respiratory illnesses of varying severity from the common cold to fatal pneumonia. Numerous coronaviruses, first discovered in domestic poultry... read more (SARS), the Middle East respiratory syndrome Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Coronaviruses are enveloped RNA viruses that cause respiratory illnesses of varying severity from the common cold to fatal pneumonia. Numerous coronaviruses, first discovered in domestic poultry... read more (MERS), and COVID-19 COVID-19 COVID-19 is an acute, sometimes severe, respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. COVID-19 was first reported in late 2019 in Wuhan, China and has since spread extensively... read more .

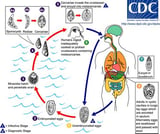

Parasites causing lung infection in developed countries include Toxocara canis or T. catis (toxocariasis Toxocariasis Toxocariasis is human infection with nematode ascarid larvae that ordinarily infect animals. Symptoms are fever, anorexia, hepatosplenomegaly, rash, pneumonitis, asthma, or visual impairment... read more  ), Dirofilaria immitis (dirofilariasis Dirofilariasis Dirofilariasis is a filarial nematode infection with Dirofilaria immitis, the dog heartworm, or other Dirofilaria species, which are transmitted to humans by infected mosquitoes. (See also Approach... read more ), and Paragonimus westermani (paragonimiasis Paragonimiasis Paragonimiasis is infection with the lung fluke Paragonimus westermani and related species. Humans are infected by eating raw, pickled, or poorly cooked freshwater crustaceans. Most infections... read more

), Dirofilaria immitis (dirofilariasis Dirofilariasis Dirofilariasis is a filarial nematode infection with Dirofilaria immitis, the dog heartworm, or other Dirofilaria species, which are transmitted to humans by infected mosquitoes. (See also Approach... read more ), and Paragonimus westermani (paragonimiasis Paragonimiasis Paragonimiasis is infection with the lung fluke Paragonimus westermani and related species. Humans are infected by eating raw, pickled, or poorly cooked freshwater crustaceans. Most infections... read more  ).

).

In children, the most common causes of pneumonia depend on age:

-

< 5 years: Most often viruses; among bacteria, S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and S. pyogenes, are common

-

≥ 5 years: Most often the bacteria S. pneumoniae, M. pneumoniae, or Chlamydia pneumoniae

Symptoms and Signs of Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Symptoms include malaise, chills, rigor, fever, cough, dyspnea, and chest pain. Cough typically is productive in older children and adults and dry in infants, young children, and older adults. Dyspnea usually is mild and exertional and is rarely present at rest. Chest pain is pleuritic and is adjacent to the infected area. Pneumonia may manifest as upper abdominal pain when lower lobe infection irritates the diaphragm. Gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) are also common. Symptoms become variable at the extremes of age. Infection in infants may manifest as nonspecific irritability and restlessness; in older patients, manifestation may be as confusion and obtundation.

Signs include fever, tachypnea, tachycardia, crackles, bronchial breath sounds, egophony (E to A change—said to occur when, during auscultation, a patient says the letter "E" and through the stethoscope the examiner hears the letter "A"), and dullness to percussion. Signs of pleural effusion Symptoms and Signs Pleural effusions are accumulations of fluid within the pleural space. They have multiple causes and usually are classified as transudates or exudates. Detection is by physical examination and... read more  may also be present. Nasal flaring, use of accessory muscles, and cyanosis are common among infants. Fever is frequently absent in older patients.

may also be present. Nasal flaring, use of accessory muscles, and cyanosis are common among infants. Fever is frequently absent in older patients.

-

Chest x-ray

-

Consideration of alternative diagnoses (eg, heart failure, pulmonary embolism)

-

Sometimes identification of pathogen

-

Evaluation of severity and risk stratification

Differential diagnosis in patients presenting with pneumonia-like symptoms includes acute bronchitis Acute Bronchitis Acute bronchitis is inflammation of the tracheobronchial tree, commonly following an upper respiratory infection that occurs in patients without chronic lung disorders The cause is almost always... read more and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is airflow limitation caused by an inflammatory response to inhaled toxins, often cigarette smoke. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and various occupational... read more  , which can be distinguished from pneumonia by the absence of infiltrates on chest x-ray. Other disorders should be considered, particularly when findings are inconsistent or not typical, such as heart failure Heart Failure (HF) Heart failure (HF) is a syndrome of ventricular dysfunction. Left ventricular failure causes shortness of breath and fatigue, and right ventricular failure causes peripheral and abdominal fluid... read more

, which can be distinguished from pneumonia by the absence of infiltrates on chest x-ray. Other disorders should be considered, particularly when findings are inconsistent or not typical, such as heart failure Heart Failure (HF) Heart failure (HF) is a syndrome of ventricular dysfunction. Left ventricular failure causes shortness of breath and fatigue, and right ventricular failure causes peripheral and abdominal fluid... read more  , organizing pneumonia, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is a syndrome of cough, dyspnea, and fatigue caused by sensitization and subsequent hypersensitivity to environmental (frequently occupational or domestic) antigens... read more

, organizing pneumonia, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is a syndrome of cough, dyspnea, and fatigue caused by sensitization and subsequent hypersensitivity to environmental (frequently occupational or domestic) antigens... read more  . The most serious common misdiagnosis is pulmonary embolism Pulmonary Embolism (PE) Pulmonary embolism (PE) is the occlusion of pulmonary arteries by thrombi that originate elsewhere, typically in the large veins of the legs or pelvis. Risk factors for pulmonary embolism are... read more

. The most serious common misdiagnosis is pulmonary embolism Pulmonary Embolism (PE) Pulmonary embolism (PE) is the occlusion of pulmonary arteries by thrombi that originate elsewhere, typically in the large veins of the legs or pelvis. Risk factors for pulmonary embolism are... read more  , which may be more likely in patients with acute onset of dyspnea, minimal sputum production, no accompanying upper respiratory infection or systemic symptoms, and risk factors for thromboembolism (see table Risk Factors for Deep Venous Thrombosis Risk Factors for Deep Venous Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism Pulmonary embolism (PE) is the occlusion of pulmonary arteries by thrombi that originate elsewhere, typically in the large veins of the legs or pelvis. Risk factors for pulmonary embolism are... read more

, which may be more likely in patients with acute onset of dyspnea, minimal sputum production, no accompanying upper respiratory infection or systemic symptoms, and risk factors for thromboembolism (see table Risk Factors for Deep Venous Thrombosis Risk Factors for Deep Venous Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism Pulmonary embolism (PE) is the occlusion of pulmonary arteries by thrombi that originate elsewhere, typically in the large veins of the legs or pelvis. Risk factors for pulmonary embolism are... read more  ); thus, testing for pulmonary embolism should be considered in patients with such symptoms and risk factors.

); thus, testing for pulmonary embolism should be considered in patients with such symptoms and risk factors.

Quantitative cultures of bronchoscopic or suctioned specimens, if they are obtained before antibiotic administration, can help distinguish between bacterial colonization (ie, presence of microorganisms at levels that provoke neither symptoms nor an immune response) and infection. However, bronchoscopy is usually done only in patients receiving mechanical ventilation or for those with other risk factors for unusual microorganisms or complicated pneumonia (eg, immunocompromise, failure of empiric therapy).

Distinguishing between bacterial and viral pneumonias is challenging. Many studies have investigated the utility of clinical, imaging, and routine blood tests, but no test is reliable enough to make this differentiation. Even identification of a virus does not preclude concomitant infection with a bacteria; therefore, antibiotics are indicated in almost all patients with a community-acquired pneumonia.

Diagnosis of etiology can be difficult. A thorough history of exposures, travel, pets, hobbies, and other exposures is essential to raise suspicion of less common organisms.

Identification of the pathogen can be useful to direct therapy and verify bacterial susceptibilities to antibiotics. However, because of the limitations of current diagnostic tests and the success of empiric antibiotic treatment, experts recommend limiting attempts at microbiologic identification (eg, cultures, specific antigen testing) unless patients are at high risk or have complications (eg, severe pneumonia, immunocompromise, asplenia, failure to respond to empiric therapy). In general, the milder the pneumonia, the less such diagnostic testing is required. Critically ill patients require the most intensive testing, as do patients in whom a antibiotic-resistant or unusual organism is suspected (eg, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, P. jirovecii) and patients whose condition is deteriorating or who are not responding to treatment within 72 hours.

Chest x-ray findings generally cannot distinguish one type of infection from another, although the following findings are suggestive:

-

Multilobar infiltrates suggest S. pneumoniae or Legionella pneumophila infection.

-

Interstitial pneumonia (on chest x-ray, appearing as increased interstitial markings and subpleural reticular opacities that increase from the apex to the bases of the lungs) suggests viral or mycoplasmal etiology.

-

Cavitating pneumonia suggests S. aureus or a fungal or mycobacterial etiology.

Blood cultures, which are often obtained in patients hospitalized for pneumonia, can identify causative bacterial pathogens if bacteremia is present. About 12% of all patients hospitalized with pneumonia have bacteremia; S. pneumoniae accounts for two thirds of these cases.

Sputum testing can include Gram stain and culture for identification of the pathogen, but the value of these tests is uncertain because specimens often are contaminated with oral flora and overall diagnostic yield is low. Regardless, identification of a bacterial pathogen in sputum cultures allows for susceptibility testing. Obtaining sputum samples also allows for testing for viral pathogens via direct fluorescence antibody testing or polymerase chain reaction (PCR), but caution needs to be exercised in interpretation because 15% of healthy adults carry a respiratory virus or potential bacterial pathogen. In patients whose condition is deteriorating and in those unresponsive to broad-spectrum antibiotics, sputum should be tested with mycobacterial and fungal stains and cultures.

Sputum samples can be obtained noninvasively by simple expectoration or after hypertonic saline nebulization (induced sputum) for patients unable to produce sputum. Alternatively, patients can undergo bronchoscopy or endotracheal suctioning, either of which can be easily done through an endotracheal tube in mechanically ventilated patients. Otherwise, bronchoscopic sampling is usually done only for patients with other risk factors (eg, immunocompromise, failure of empiric therapy).

Urine testing for Legionella antigen and pneumococcal antigen is now widely available. These tests are simple and rapid and have higher sensitivity and specificity than sputum Gram stain and culture for these pathogens. Patients at risk of Legionella pneumonia (eg, severe illness, failure of outpatient antibiotic treatment, presence of pleural effusion, active alcohol abuse, recent travel) should undergo testing for urinary Legionella antigen, which remains present long after treatment is initiated, but the test detects only L. pneumophila serogroup 1 (70% of cases).

The pneumococcal antigen test is recommended for patients who are severely ill; have had unsuccessful outpatient antibiotic treatment; or who have pleural effusion, active alcohol abuse, severe liver disease, or asplenia. This test is especially useful if adequate sputum samples or blood cultures were not obtained before initiation of antibiotic therapy. A positive test can be used to tailor antibiotic therapy, though it does not provide antimicrobial susceptibility.

Mortality varies to some extent by pathogen. Mortality rates are highest with gram-negative bacteria and CA-MRSA. However, because these pathogens are relatively infrequent causes of community-acquired pneumonia, S. pneumoniae remains the most common cause of death in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Atypical pathogens such as Mycoplasma have a good prognosis. Mortality is higher in patients who do not respond to initial empiric antibiotics and in those whose treatment regimen does not conform with guidelines.

-

Risk stratification for determination of site of care

-

Antibiotics

-

Antivirals for influenza or varicella

-

Supportive measures

Intensive care unit (ICU) admission is required for patients who

-

Need mechanical ventilation

-

Have hypotension (systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mm Hg) that is unresponsive to volume resuscitation

Other criteria, especially if ≥ 3 are present, that should lead to consideration of ICU admission include

-

Hypotension requiring fluid support

-

Respiratory rate >30/minute

-

PaO2/fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) < 250

-

Multilobar pneumonia

-

Confusion

-

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) > 19.6 mg/dL (> 7 mmol/L)

-

Leukocyte count < 4000 cells/microL (< 4 × 109/L)

-

Platelet count < 100,000/microL (< 100 × 109/L)

-

Temperature < 36° C

The Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) is the most studied and validated prediction rule. However, because the PSI is complex and requires several laboratory assessments, simpler rules such as CURB-65 are usually recommended for clinical use. Use of these prediction rules has led to a reduction in unnecessary hospitalizations for patients who have milder illness.

In CURB-65, 1 point is allotted for each of the following risk factors:

-

Confusion

-

Uremia (BUN ≥19 mg/dL [6.8 mmol/L])

-

Respiratory rate > 30 breaths/minute

-

Systolic Blood pressure < 90 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≤ 60 mm Hg

-

Age ≥ 65 years

Scores can be used as follows:

-

0 or 1 points: Risk of death is < 3%. Outpatient therapy is usually appropriate.

-

2 points: Risk of death is 9%. Hospitalization should be considered.

-

≥ 3 points: Risk of death is 15 to 40%. Hospitalization is indicated, and, particularly with 4 or 5 points, ICU admission should be considered.

![]()

For children, treatment depends on age, previous vaccinations, and whether treatment is outpatient or inpatient.

For children treated as outpatients, treatments are dictated by age:

-

< 5 years: Amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanate is usually the drug of choice. If epidemiology suggests an atypical pathogen as the cause and clinical findings are compatible, a macrolide (eg, azithromycin, clarithromycin) can be used instead. Some experts suggest not using antibiotics if clinical features strongly suggest viral pneumonia.

-

≥ 5 years: Amoxicillin or (particularly if an atypical pathogen cannot be excluded) amoxicillin plus a macrolide. Amoxicillin/clavulanate is an alternative. If the cause appears to be an atypical pathogen, a macrolide alone can be used.

For children treated as inpatients, antibiotic therapy tends to be more broad-spectrum and depends on the child's previous vaccinations:

-

Fully immunized (against S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae type b): Ampicillin or penicillin G (alternatives are ceftriaxone or cefotaxime). If MRSA is suspected, vancomycin or clindamycin is added. If an atypical pathogen cannot be excluded, a macrolide is added.

-

Not fully immunized: Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime (alternative is levofloxacin). If MRSA is suspected, vancomycin or clindamycin is added. If an atypical pathogen cannot be excluded, a macrolide is added.

With empiric treatment, 90% of patients with bacterial pneumonia improve. Improvement is manifested by decreased cough and dyspnea, defervescence, relief of chest pain, and decline in white blood cell count. Failure to improve should trigger suspicion of

-

An unusual organism

-

Resistance to the antimicrobial used for treatment

-

Empyema

-

Coinfection or superinfection with a 2nd infectious agent

-

An obstructive endobronchial lesion

-

Immunosuppression

-

Metastatic focus of infection with reseeding (in the case of pneumococcal infection)

-

Nonadherence to treatment (in the case of outpatients)

-

Wrong diagnosis (ie, a noninfectious cause of the illness such as acute hypersensitivity pneumonitis)

When usual therapy has failed, consultation with a pulmonary and/or infectious disease specialist is indicated.

Antiviral therapy may be indicated for select viral pneumonias. Ribavirin is not used routinely for respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia in children or adults but may be used occasionally in high-risk children age < 24 months.

For influenza, oseltamivir 75 mg orally twice a day or zanamivir 10 mg inhaled twice a day started within 48 hours of symptom onset and given for 5 days reduce the duration and severity of symptoms in patients who develop influenza infection. Alternatively, baloxavir started within 48 hours of symptom onset can be given in a single dose of 40 mg for patients 40 to 80 kg; 80 mg is used for patients ≥ 80 kg. In patients hospitalized with confirmed influenza infection, observational studies suggest benefit even 48 hours after symptom onset.

Acyclovir 5 to 10 mg/kg IV every 8 hours for adults or 250 to 500 mg/m2 body surface area IV every 8 hours for children is recommended for varicella lung infections. Though pure viral pneumonia does occur, superimposed bacterial infections are common and require antibiotics directed against S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and S. aureus.

Follow-up x-rays are generally not recommended in patients whose pneumonia resolves clinically as expected. Resolution of radiographic abnormalities can lag behind clinical resolution by several weeks. Chest x-ray should be considered in patients with pneumonia symptoms that do not resolve or that worsen over time.

![]()

-

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) is recommended for children age 2 months to 2 years and for adults ≥ 19 years with certain comorbid (including immunocompromising) conditions and for adults ≥ 65 years based on shared decision-making between clinician and patient.

-

Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) is given to all adults ≥ 65 years and to any patient ≥ 2 years who has risk factors for pneumococcal infections, including but not limited to those with underlying heart, lung, or immune system disorders and those who smoke.

The full list of indications for both pneumococcal vaccines can be found at the CDC website. Recommendations for other vaccines, such as H. influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine Haemophilus influenzae Type b (Hib) Vaccine Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccines help prevent Haemophilus infections but not infections caused by other strains of H. influenzae bacteria. H. influenzae causes many childhood infections... read more (for patients < 2 years), varicella vaccine Varicella Vaccine Varicella vaccination provides effective protection against varicella (chickenpox). It is not known how long protection against varicella lasts. But, live-virus vaccines, like the varicella... read more (for patients < 18 months and a later booster vaccine), and influenza vaccine Influenza Vaccine Based on recommendations by the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), vaccines for influenza are modified annually to include the most prevalent... read more (annually for everyone ≥ 6 months and especially for those at higher risk of developing serious flu-related complications), can also be found at the CDC website. This higher risk group includes people ≥ 65 years and people of any age with certain chronic medical conditions (such as diabetes, asthma, or heart disease), pregnant women, and young children.

In high-risk patients who are not vaccinated against influenza and household contacts of patients with influenza, oseltamivir 75 mg orally once/day or zanamivir 10 orally mg once/day can be given for 2 weeks. If started within 48 hours of exposure, these antivirals may prevent influenza (although resistance has been described for oseltamivir).

-

Community-acquired pneumonia is a leading cause of death in the United States and around the world.

-

Common symptoms and signs include cough, fever, chills, fatigue, dyspnea, rigors, sputum production, and pleuritic chest pain.

-

Treat patients with mild or moderate risk pneumonia with empiric antibiotics without testing designed to identify the underlying pathogen.

-

Hospitalize patients with multiple risk factors, as delineated by risk assessment tools.

-

Consider alternate diagnoses, including pulmonary embolism, particularly if pneumonia-like signs and symptoms are not typical.

The following are English-language resources that may be useful. Please note that The Manual is not responsible for the content of these resources.

Which Terms Are Used To Identify The Lobes Of The Right Lung? Select All That Apply.

Source: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/pulmonary-disorders/pneumonia/community-acquired-pneumonia

Posted by: robinsonconereven68.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Terms Are Used To Identify The Lobes Of The Right Lung? Select All That Apply."

Post a Comment